Today’s Comfortable Gospel

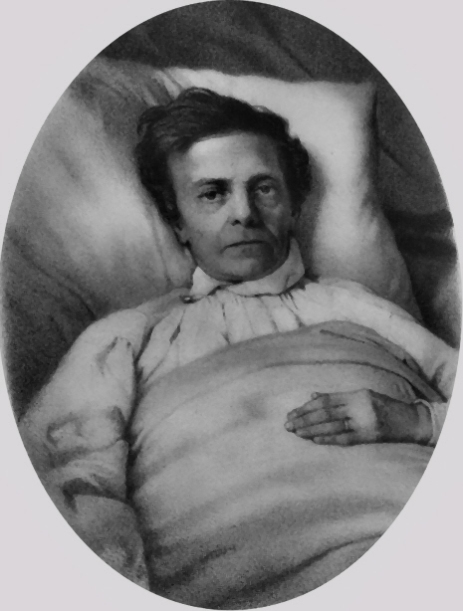

By Adolphe Monod (1802-1856)

“Saint Paul: Changing Our World For Christ,” pages 64-66

Solid Ground Christian Books

Yes, my brothers, since the day when Jesus redeemed us on a cross, everything that is great and powerful and beneficial is also solemn. All the seeds of life and regeneration are sown in suffering and death. In order to stir even the least believing among you to salvation, do you know what I would like? I would like to have Paul climb into this pulpit, emaciated from fasting, worn out by fatigue, exhausted from watches, languished from prison, and mutilated by the rods of Philippi and the stones of Lystra. Imagine what an opening to his discourse this sight, those memories would provide. What weight, what savor they would lend to the least of his spoken words! What power!

No minister of the gospel will ever attain such power if he is faithful in today’s understanding of the term yet living in well-being – if he is a stranger to suffering, if he is drawing abundantly from the sweet things of personal, domestic, and public life, if he is honored, cherished, and sought after by all. These gospel ministers of well-being, alas, do we need to go very far to seek them? If we were something other than that, how would the current generation of God’s children have given birth to us, how would it bear with us? Is this not the generation of well-being?

It has been noted in our day, unlike previous eras, it is in the comfortable classes of society that the gospel has made the greatest progress. Let us add that in order to penetrate those classes, the gospel has been made in their image. The Christianity that is lived by the comfortable classes is as comfortable as they are. For in the end, what does it cost to be a Christian today – I mean an orthodox Christian, an irreproachable Christian according to today’s concept of a Christian?

This used to be a dreadful question. What did it cost to be a Christian? Depending on the era, it might cost the sacrifice of well-being, or of fortune, or of honor, or of family, or of life. With us, let us agree, things are not so stark, and does not this difference, which has its merciful side as it relates to the Lord, also have a serious and almost frightening side as it relates to us, my brothers and sisters in Jesus Christ?

It is written, “Whoever does not bear his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:27). Very well, where is your cross? What are the sacrifices, the bitter things, the humiliations to which your faith condemns you? In addition – above all, weigh this question – what are the pleasures, the delights, the vanities with which your gospel cannot be accommodated?

No, neither a life of frivolity nor a life of laziness can be allied with the Christian enterprise I have in view in these discourses. If you have it on your heart to contribute to the regeneration of the church and society, know for certain that you will never be able to do so without a serious, humble, and crucified life. Here we do not need another Jabez, whose prayer is, “Oh that you would bless me and enlarge my border and… keep me from… pain!” (1 Chronicles 4:10). We need a Saint Paul, “always carrying in the body the death of Jesus” ( 2 Corinthians 4:10).

Am I mistaken, my brothers, in thinking that more than one among you, running ahead of my exhortations, has secretly sighed after such a life of dying that is so bitter and yet so powerful? May a generation rise up that is more able than we are to respond to the holy work being proposed to us! And if, in order to bring it to birth, the earth that bears us is not sufficiently watered by the tears of the holy apostle, may it be so at least by the blood of the cross!

Biographical Sketch (pages 9-10)

Adolphe Monod (1802-1856) has rightly been called “The Voice of the Awakening.” Those who came out of curiosity to hear the preaching of a celebrated orator would often leave the service pierced to the heart by his message, while the mature Christians in his congregations came back again and again to be transported by his preaching into the very presence of God and to have their faith stretched and challenged. Others, including Adolphe’s older brother, Frederic, were more influential as leaders of the Awakening that swept across France and Switzerland in the early 19th century, but none could expound the central core of its faith quite as clearly or persuasively or appealingly as Adolphe Monod.

Yet Monod’s faith did not come without a struggle. He was descended from Protestant ministers and received a clear call to the ministry at age fourteen, but the faith he grew up with was more formal than vibrant. In 1820 he entered seminary in Geneva, where the varied theological viewpoints soon left him in a state of spiritual confusion. He was often drawn toward the teaching of the Awakening, especially as presented by a Scotsman, Thomas Erskine, but his reason could not accept all of its teachings. Still confused, he accepted ordination in 1824.

Confusion turned to crisis when he agreed to pastor a group of French-speaking Protestants in Naples. He knew he could not express his doubts to the congregation, but his natural candor recoiled at preaching something he did not yet believe. Family members prayed earnestly for him, and once again he received help through a visit by Thomas Erskine.

Eventually, on July 21, 1827, he reached a state of peace. “I wanted to make my own religion, instead of taking it from God…. I was without God and burdened with my own well-being, while now I have a God who carries the burden for me. That is enough.” He still had questions, but he knew he would find the answers in the pages of the Bible.

Shortly thereafter he was called to join the pastoral staff of the large but worldly Reformed Church in Lyon, where his bold, gospel-centered preaching soon drew opposition. He was told not to preach salvation by grace; he refused. They demanded his resignation; he refused. After much unpleasantness, the elders secured the government’s permission to dismiss him, but a group of evangelical Christians who had already left the national church asked him to establish an independent congregation in Lyon. He served there until until an unexpected call led him to the national church’s seminary in Montauban. A decade later, in 1847, he returned to the pastorate, serving the Reformed Church in Paris. Quite ill and diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1855, he began holding small communion services in his home. These continued until his death on April 6, 1856, with his children writing down the brief meditations he gave.

Those facts, however, fail to truly capture the spirit of the man. His was a strong and passionate faith, in part because of his early spiritual struggles. He was also a man of great integrity, a keen mind, and a deeply caring, pastoral heart. All of these qualities were augmented and set off by his natural gift for speaking. Yet even as his renown grew, Adolphe Monod remained a truly humble man. A week before his death he said, “I have a Savior! He has freely saved me through his shed blood, and I want it to be known that I lean uniquely on that poured-out blood. All my righteous acts, all my works which have been praised, all my preaching that has been appreciated and sought after – all that is in my eyes only filthy rags.”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qlypwnq5WY8&w=853&h=480]