Connolly, Waugh, Betjeman, to name only a few, have pungently described the disenchantments of schooldays… I do not wish to appear less competent than my contemporaries in making creep the flesh of the epicure of sado-masochistic school reminiscence. —Anthony Powell: Infants of the Spring

“Today, as a middle-aged man of 56, I’m not particularly good-looking. But as a boy, I was considered “pretty”, and in the boarding-school world that I grew up in, that meant only one thing: being regularly molested by other boys at prep school and again at the public school in Hampshire, the school to which generations of my family had gone and my parents had a close connection.

So I followed John Smyth to the shed, the man I’d met through the school’s then newly revitalised Christian Forum. A shed that also doubled as the changing room for his swimming pool. Inside, I saw the pile of canes in the corner, and I felt my heart thump in shock. “Please take off all your clothes,” he said calmly.”

-John Smyth, the School Predator Who Beat Me for Five Years

The Telegraph (Link)

“Lady Smith – speaking at a preliminary hearing of the inquiry at the Court of Session in Edinburgh last week – also said that more than 100 locations where abuse is said to have taken place have been identified.

In a statement, she urged anyone with information about abuse to come forward.

She said: “So far, we have identified more than 100 locations where abuse of children is said to have taken place but we know that there are many more than that.

“The inquiry team is currently investigating over 60 residential care establishments for children in order to gather, from those who ran them and others, evidence about how children who were being cared for in a range of different settings and by a number of different types of care organisations were treated.””

Former Dumbarton Boarding School Probed in Historic Child Abuse Inquiry

The Daily Record (Link)

“When I was an adolescent schoolboy at boarding school in the 1950s we all knew where we stood on the intriguing issues of sex and sexuality that were opening up in our lives.”

-John Smyth, “Why Choose Heterosexuality”

The recent attention that has been focused on the alleged abuser John Smyth and the subsequent claim by his son, PJ Smyth, that he had no knowledge of the abuse caused me to think of two books I have read, one by Christopher Hitchens, the other by C.S Lewis, in which they spoke of the abuse they encountered while they attended boarding schools in the UK. I have quoted at length from the two books below. It seems that sick, twisted, sexual perverts have been drawn in large numbers to boarding schools.

I would be interested in knowing if John Smyth and PJ Smyth were themselves, victims of abuse, when they were students in boarding schools.

Hitch-22: A Memoir

Christopher Hitchens

Fragments from an Education

Nobody could have been less chauvinistic than Ian Watt but then, he was one of the few survivors of The Bridge On The River Kwai, The Burma Railroad, Changi Jail in Singapore, and other Hirohito horrors that I still capitalize in my mind. He admitted later that, detecting other people’s reserve after returning home from these wartime nightmares, he had developed a manner of discussing them apotropaically, as it were, so as to defuse them a bit. And he told me the following tale, which I set down with the hope that it captures his memorably laconic tone of voice:

“Well, we were in a cell that was probably built for six but was holding about sixteen of us. There wasn’t much food and we hadn’t been given any water for quite a while. The heat was absolutely ferocious. Dysentery had begun to take its toll, which was distinctly disagreeable at such close quarters.

Added to this unpleasantness, we could hear one of our number being rather badly beaten by the Japanese guards, with rifle-butts it seemed, in their guardroom down the corridor. At this rather trying moment one of my young subalterns, who’d managed to fall asleep, started screaming and flailing and yelling. He was shouting: “No, no— please don’t… Not any more, not again, Oh God please.” Hideous noises like that. I had to take a snap decision to prevent panic, so I ordered the sergeant to slap him and wake him up. When he came to, he apologized for being a bore but brokenly confessed that he’d dreamed he was back at Tonbridge.”

My laughter at this, for all its brilliant timing and understatement, was very slightly awkward. Watt went on to recall an interview with that other old Asia hand E.M. Forster, in which he’d been asked, as an “old boy” of Tonbridge School, whether he would ever agree to write an article for the school magazine. “Only,” said the author of A Passage to India, “if it could be against compulsory games.” The very phrase “compulsory games” had automatic resonance for me, bringing back not merely the memory of freezing soccer and rugby pitches, and of the gloating sadists who infested the changing-rooms that were the aftermath of these pointless contests, but also W.H. Auden’s suggestive line in one of his greatest poems [“ 1 September 1939”]:

And helpless governors wake / To resume their compulsory game…

It was indeed Auden— who had been a master at such a school as well as having been a pupil at one— who had said that the experience had given him an instinctive understanding of what it would be like to live under fascism. (He had also said, when told by the headmaster that only “the cream” attended the school: “yes I know what you mean— thick and rich.”)

Tonbridge was a synonym for those Spartan schools where the empire, the church, the cricket field, the war memorial, and the monarchy were, well, sovereign. The blue-eyed boy, small for his age and with rather feminine eyelashes, who is indifferent to sports and happiest in the library is… buggered. Not to say beaten and bullied.

All this Yvonne saw, or I suppose I should say she somehow intuited, at a glance. My poor parents. During my infancy in Scotland I had had to be taken away from one school, with the forbidding name of Inchkeith, when it had been noticed at home that I cowered and flung up a protective arm every time an adult male came near me. Investigation showed the place to be a minor hell of flagellation and “abuse” (such a pathetic euphemism for the real thing) so I was taken away and put in a nearer establishment named Camdean. On my first day there I was hit between the eyes with a piece of slate during an exchange of views with the Catholic school across the road, with whom our hardened Protestant gangs were at odds. Innocent of any interest in this quarrel, I nonetheless bear the faint scar of it, above the bridge of my nose, to this day.

For the next five years, by now removed southward to Devon, where my Fifeshire accent was duly knocked out of me, I underwent an experience that was once commonplace but has now become as remote and obscure in its way as travel by steam train. Indeed, I often have difficulty convincing my graduate students that I really did go off to prep school at the age of eight, from station platforms begrimed with coal dust and echoing to the mounting “whomp, whomp, woof, woof” of the pistons beginning to turn, as my own “trunk” and “tuck box” were loaded into a “luggage car.”

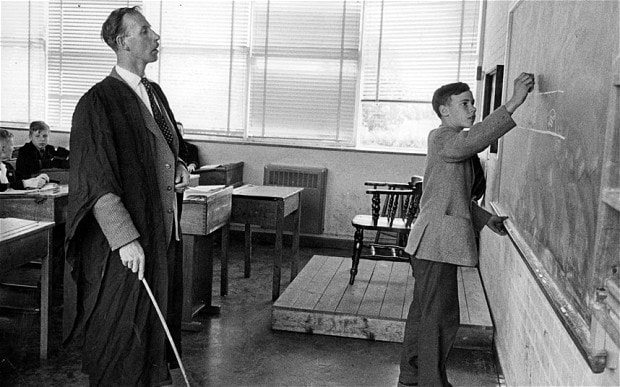

Not only that, but that I wore corduroy shorts in all weathers, blazers with a school crest on Sundays, slept in a dormitory with open windows, began every day with a cold bath (followed by the declension of Latin irregular verbs), wolfed lumpy porridge for breakfast, attended compulsory divine service every morning and evening, and kept a diary in which— in a special code— I recorded the number of times when I was left alone with a grown-up man, who was perhaps four times my weight and five times my age, and bent over to be thrashed with a cane.

The strange thing, or so I now think, was the way in which it didn’t feel all that strange. The fictions and cartoons of Nigel Molesworth, of Paul Pennyfeather in Waugh’s Decline and Fall, and numberless other chapters of English literary folklore have somehow made all this mania and ritual appear “normal,” even praiseworthy. Did we suspect our schoolmasters— not to mention their weirdly etiolated female companions or “wives,” when they had any— of being in any way “odd,” not to say queer?

We had scarcely the equipment with which to express the idea, and anyway what would this awful thought make of our parents, who were paying— as we were so often reminded— a princely sum for our privileged existences? The word “privilege” was indeed employed without stint. Yes, I think that must have been it. If we had not been certain that we were better off than the oafs and jerks who lived on housing estates and went to state-run day schools, we might have asked more questions about being robbed of all privacy, encouraged to inform on one another, taught how to fawn upon authority and turn upon the vulnerable outsider, and subjected at all times to rules which it was not always possible to understand, let alone to obey. I think it was that last point which impressed itself upon me most, and which made me shudder with recognition when I read Auden’s otherwise overwrought comparison of the English boarding school to a totalitarian regime. The conventional word that is employed to describe tyranny is “systematic.” The true essence of a dictatorship is in fact not its regularity but its unpredictability and caprice; those who live under it must never be able to relax, must never be quite sure if they have followed the rules correctly or not. (The only rule of thumb was: whatever is not compulsory is forbidden.) Thus, the ruled can always be found to be in the wrong. The ability to run such a “system” is among the greatest pleasures of arbitrary authority, and I count myself lucky, if that’s the word, to have worked this out by the time I was ten.

Later in life I came up with the term “micro-megalomaniac” to describe those who are content to maintain absolute domination of a small sphere. I know what the germ of the idea was, all right. “Hitchens, take that look off your face!” Near-instant panic. I hadn’t realized I was wearing a “look.” (Face-crime!) “Hitchens, report yourself at once to the study!” “Report myself for what, sir?” “Don’t make it worse for yourself, Hitchens, you know perfectly well.” But I didn’t. And then: “Hitchens, it’s not just that you have let the whole school down. You have let yourself down.” To myself I was frantically muttering: Now what? It turned out to be some dormitory sex-game from which— though the fools in charge didn’t know it— I had in fact been excluded. But a protestation of my innocence would have been, as in any inquisition, an additional proof of guilt.

There were other manifestations, too. There was nowhere to hide. The lavatory doors sometimes had no bolts. One was always subject to invigilation, waking and sleeping. Collective punishment was something I learned about swiftly: “Until the offender confesses in public,” a giant voice would intone, “all your ‘privileges’ will be withdrawn.” There were curfews, where we were kept at our desks or in our dormitories under a cloud of threats while officialdom prowled the corridors in search of unspecified crimes and criminals. Again I stress the matter of sheer scale: the teachers were enormous compared to us and this lent a Brobdingnagian aspect to the scene. In seeming contrast, but in fact as reinforcement, there would be long and “jolly” periods where masters and boys would join in scenes of compulsory enthusiasm— usually over the achievements of a sports team— and would celebrate great moments of victory over lesser and smaller schools. I remember years later reading about Stalin that the intimates of his inner circle were always at their most nervous when he was in a “good” mood, and understanding instantly what was meant by that.

If my parents knew what really went on at the school, I used to think (not being the first little boy to imagine that my main job was that of protecting parental innocence), they would faint from the shock. So I would be staunch and defend them from the knowledge. Meanwhile, and speaking of books, the school possessed its very own library, and several of the masters had private collections of their own, to which one might be admitted (not always without risk to these men’s immortal souls) as a great treat.

This often feels as if it happened to somebody else yet I can be sure it did not because I can recall the element of sadomasochism so well. Awareness of this is no doubt innate in all of us, and I suppose a case could be made for teaching it to children as part of “sex education” or the facts of life, but I had to sit in a freezing classroom at first light, at a tender age, and hear my silver-haired Latin teacher Mr. Witherington approach the verge of tears as he digressed from the study of Caesar and Tacitus and told us with an awful catch in his voice of the way in which he had been flogged at Eastbourne School. And that same brutish academy, we thought as we squirmed our tiny rears on the wooden benches, was one of those to which we were supposed to aspire. I think I wish I had not been introduced so early to the connection between obscure sexual excitement and the infliction— or the reception— of pain.

Looking back, it is the masochistic element that impresses me more than the sadistic one. It’s relatively easy to see why people want to exert power over others, but what fascinated me was the way in which the victims colluded in the business. Bullies would acquire a personal squad of toadies with impressive speed and ease. The more tyrannical the schoolmaster, the more those who lived in fear of him would rush to placate him and to anticipate his moods. Small boys who were ill-favored, or “out of favor” with authority, would swiftly attract the derision and contempt of the majority as well. I still writhe when I think how little I did to oppose this. My tongue sharpened itself mainly in my own defense.

My memory of how that felt was as vivid as possible. Gratitude for having been spared, vague guilt at an offense I had not known about or guessed at (thought crime!), strong fear of a repeat offense that I could not predict or avoid, the emotion of relief colliding with the feeling of unworthiness. And fear of the all-powerful boss, too, combined with an awareness of all the blessings and forgiveness which it was in his Almighty power to bestow. One of the most awful reproaches in the school’s arsenal of psychological torture— Orwell catches it very well in his essay “Such, Such Were the Joys”— was the one about one’s sickly ingratitude: the selfish refusal to shape up after all that had been done on one’s behalf. Of course I now recognize this as the working model, drawn from monotheistic religion, where love is compulsory and must be offered to a higher being whom one must necessarily also fear. This moral blackmail is based on a quintessential servility. The fact that the headmaster held the prayerbook and the Bible during the services also drove home to me the obvious fact that religion is an excellent reinforcement of shaky temporal authority.

Hugh Wortham, my huge and dominating headmaster and introducer to the dark arts of corporal punishment, was a lifelong bachelor, but some of the local mothers found him handsome, and Yvonne gaily said that he put her in mind of Rex Harrison. His huge, brawny, furry arms and his immense horseshoes of teeth made him seem almost gorilla-like to me and a bold contrast to the rather slight figure of the Commander. His rages would shake the windows and make small boys turn white: his “good moods” were a hell to endure and a challenge to manipulate. Heaven knows what he’d been through sexually: he himself didn’t stoop to “fiddling” with any of us but if you were occasionally favored, as I occasionally was, you would be given a copy of David Blaize or one of the Jeremy novels and asked if you’d care to read it “in your free time.” Though I didn’t have the vocabulary for this in those days, I now know quite a lot about E.F. Benson and Hugh Walpole and I sensed even then that this was the world of the smoldering and yearning and repressed adult homosexual, fixated on his own schooldays and probably most attracted to those who are themselves blithely unaware of the intensity of the attention.

Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life

C.S. Lewis

Concentration Camp

Arithmetic with Coloured Rods.

CLOP-CLOP-CLOP-CLOP . . . we are in a four-wheeler rattling over the uneven squaresets of the Belfast streets through the damp twilight of a September evening, 1908; my father, my brother, and I. I am going to school for the first time. We are in low spirits. My brother, who has most reason to be so, for he alone knows what we are going to, shows his feelings least. He is already a veteran. I perhaps am buoyed up by a little excitement, but very little. The most important fact at the moment is the horrible clothes I have been made to put on. Only this morning— only two hours ago— I was running wild in shorts and blazer and sand shoes. Now I am choking and sweating, itching too, in thick dark stuff, throttled by an Eton collar, my feet already aching with unaccustomed boots. I am wearing knickerbockers that button at the knee. Every night for some forty weeks of every year and for many a year I am to see the red, smarting imprint of those buttons in my flesh when I undress. Worst of all is the bowler hat, apparently made of iron, which grasps my head. I have read of boys in the same predicament who welcomed such things as signs of growing up; I had no such feeling. Nothing in my experience had ever suggested to me that it was nicer to be a schoolboy than a child or nicer to be a man than a schoolboy. My brother never talked much about school in the holidays. My father, whom I implicitly believed, represented adult life as one of incessant drudgery under the continual threat of financial ruin. In this he did not mean to deceive us. Such was his temperament that when he exclaimed, as he frequently did, “There’ll soon be nothing for it but the workhouse,” he momentarily believed, or at least felt, what he said. I took it all literally and had the gloomiest anticipation of adult life. In the meantime, the putting on of the school clothes was, I well knew, the assumption of a prison uniform.

The school, as I first knew it, consisted of some eight or nine boarders and about as many day boys. Organized games, except for endless rounders in the flinty playground, had long been moribund and were finally abandoned not very long after my arrival. There was no bathing except one’s weekly bath in the bathroom. I was already doing Latin exercises (as taught by my mother) when I went there in 1908, and I was-still doing Latin exercises when I left there in 1910; I had never got in sight of a Roman author. The only stimulating element in the teaching consisted of a few well-used canes which hung on the green iron chimney piece of the single schoolroom. The teaching staff consisted of the headmaster and proprietor (we called him Oldie), his grown-up son (Wee Wee), and an usher. The ushers succeeded one another with great rapidity; one lasted for less than a week. Another was dismissed in the presence of the boys, with a rider from Oldie to the effect that if he were not in Holy Orders he would kick him downstairs. This curious scene took place in the dormitory, though I cannot remember why. All these ushers (except the one who stayed less than a week) were obviously as much in awe of Oldie as we.

Oldie lived in a solitude of power, like a sea captain in the days of sail. No man or woman in that house spoke to him as an equal. No one except Wee Wee initiated conversation with him at all.

I myself was rather a pet or mascot of Oldie’s— a position which I swear I never sought and of which the advantages were purely negative. Even my brother was not one of his favorite victims. For he had his favorite victims, boys who could do nothing right. I have known Oldie enter the schoolroom after breakfast, cast his eyes round, and remark, “Oh, there you are, Rees, you horrid boy. If I’m not too tired I shall give you a good drubbing this afternoon.” He was not angry, nor was he joking. He was a big, bearded man with full Ups like an Assyrian king on a monument, immensely strong, physically dirty. Everyone talks of sadism nowadays but I question whether his cruelty had any erotic element in it. I half divined then, and seem to see clearly now, what all his whipping boys had in common. They were the boys who fell below a certain social status, the boys with vulgar accents. Poor P.— dear, honest, hard-working, friendly, healthily pious P.— was flogged incessantly, I now think, for one offense only; he was the son of a dentist. I have seen Oldie make that child bend down at one end of the schoolroom and then take a run of the room’s length at each stroke; but P. was the trained sufferer of countless thrashings and no sound escaped him until, toward the end of the torture, there came a noise quite unlike a human utterance. That peculiar croaking or rattling cry, that, and the gray faces of all the other boys, and their deathlike stillness are among the memories I could willingly dispense with.

Except at geometry (which he really liked) it might be said that Oldie did not teach at all. He called his class up and asked questions. When the replies were unsatisfactory he said in a low, calm voice, “Bring me my cane. I see I shall need it.” If a boy became confused Oldie flogged the desk, shouting in a crescendo, “Think— Think— THINK!!” Then, as the prelude to execution, he muttered, “Come out, come out, come out.” When really angry he proceeded to antics; worming for wax in his ear with his little finger and babbling, “Aye, aye, aye, aye . . .” I have seen him leap up and dance round and round like a performing bear.

…And all this, I doubt not, with extreme conscientiousness and even some anguish. It might, perhaps, have been expected that this story of his would presently be blown away by the real story which we had to tell after we had gone to Belsen. But this did not happen. I believe it rarely happens. If the parents in each generation always or often knew what really goes on at their sons’ schools, the history of education would be very different. At any rate, my brother and I certainly did not succeed in impressing the truth on our father’s mind. For one thing (and this will become clearer in the sequel) he was a man not easily informed. His mind was too active to be an accurate receiver. What he thought he had heard was never exactly what you had said. We did not even try very hard. Like other children, we had no standard of comparison; we supposed the miseries of Belsen to be the common and unavoidable miseries of all schools. Vanity-helped to tie our tongues. A boy home from school (especially during that first week when the holidays seem eternal) likes to cut a dash. He would rather represent his master as a buffoon than an ogre. He would hate to be thought a coward and a crybaby, and he cannot paint the true picture of his concentration camp without admitting himself to have been for the last thirteen weeks a pale, quivering, tear-stained, obsequious slave. We all like showing scars received in battle; the wounds of the ergastulum, less. My father must not bear the blame for our wasted and miserable years at Oldie’s; and now, in Dante’s words, “to treat of the good that I found there.”

…Intellectually, the time I spent at Oldie’s was almost entirely wasted; if the school had not died, and if I had been left there two years more, it would probably have sealed my fate as a scholar for good. Geometry and some pages in West’s English Grammar (but even those I think I found for myself) are the only items on the credit side. For the rest, all that rises out of the sea of arithmetic is a jungle of dates, battles, exports, imports and the like, forgotten as soon as learned and perfectly useless had they been remembered.

There was also a great decline in my imaginative life. For many years Joy (as I have defined it) was not only absent but forgotten. My reading was now mainly rubbish;

…All security seemed to be taken from me; there was no solid ground beneath my feet. It is significant that at this time if I woke in the night and did not immediately hear my brother’s breathing from the neighboring bed, I often suspected that my father and he had secretly risen while I slept and gone off to America— that I was finally abandoned.

…The machinery of the Garuda Stone really serves to bring out in their true colors (which would otherwise seem exaggerated) the sensations which every boy had on passing from the warmth and softness and dignity of his home life to the privations, the raw and sordid ugliness, of school.